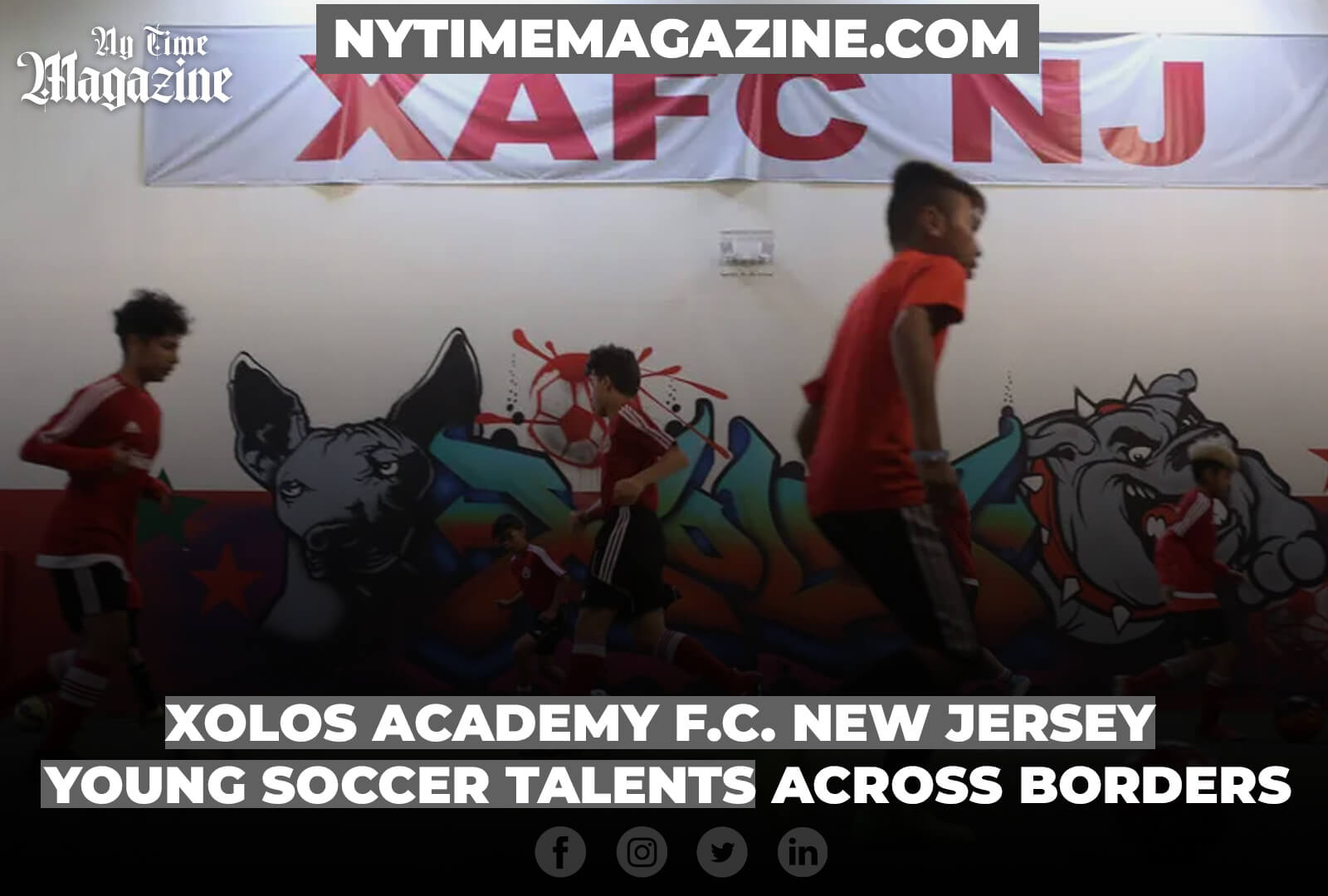

In Cliffwood, New Jersey, a group of young boys dressed in red soccer uniforms walked into an old warehouse on a rainy Saturday. Once a storage space for the affluent residents’ antique cars in this community along the Raritan Bay, the warehouse now serves a different purpose. Academias Cerca de Mi Ubicación: The Xolos Academy F.C. New Jersey, affiliated with the Mexican top-flight team Club Tijuana, transformed this old warehouse into a synthetic turf field adorned with logos and photos, creating a field of dreams.

While soccer is taught here, the academy’s real mission is to provide an opportunity for the children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the area. These players, often ignored by mainstream U.S. soccer, face financial hurdles preventing their talents from receiving the necessary training and exposure.

“Some of these players haven’t been able to shine because they can’t afford to play the game they love,” said Joe DiMauro, an experienced coach who leads the academy. It is Club Tijuana’s fifth U.S. affiliate and the first in the northeastern United States.

These academies are part of Club Tijuana’s effort to connect with fans on both sides of the Mexico-U.S. border. Xolos was the first team in Mexico’s top-tier league, Liga MX, to handle its public relations bilingually. The team has been actively recruiting both fans and players from the United States since its inception in 2007.

“Each of our academies in the United States has the necessary coaching staff to do the job, which helps elevate the players’ level,” said Roberto Cornejo, the sporting director of Club Tijuana, which includes four Americans in its 22-player first team. “We have a lot of faith in our youth system, and we will continue to develop these kids to give them the opportunity to play at the highest level.”

Academias Cerca de Mi Ubicación, Tab Ramos, a former U.S. national team star who grew up in New Jersey and now coaches the U.S. U-20 national team, understands the area and the challenges young Latino soccer players face to get noticed. He knows that finding and nurturing as many talents as possible is not only crucial for the players but also for the U.S. Soccer Federation.

“As long as there are more clubs and people catering to every kind of market, especially the Latino market, it’s more positive for our game,” Ramos pointed out.

During our visit on that rainy Saturday, as the rain poured down outside, DiMauro sat comfortably in the warehouse, sipping coffee behind a small desk, watching some of his recruits warming up to the rhythm of Elvis Crespo’s “Suavemente.”

“We look for talent in places that other academies aren’t interested in,” DiMauro said. “We spent years training kids in the neighborhood league for little or no money to develop them as soccer players, and now many are coming back because they know they can compete on a bigger and much more affordable stage.”

DiMauro reached into a drawer and pulled out a bag full of crumpled one and five-dollar bills, along with a handful of quarters: nearly $540 in tips, almost the cost of an enrollment fee.

“These are tips from someone who worked hard for them. It’s the kind of payment many of our players’ parents, who are waiters, dishwashers, and laborers that don’t speak English, give us,” DiMauro said. “They are hardworking people hoping we can help their children have a better life through soccer.”

Amando Moreno, a 21-year-old forward playing for Club Tijuana, is a local player who managed to escape the shadows. Moreno, who grew up in Old Bridge, New Jersey, and played in the academy, left Marlboro High School after three years to sign a professional contract with the Red Bulls at the age of 17. He moved to Club Tijuana the following year, primarily playing in national cup matches until he made his Liga MX debut in April 2016.

“I was a kid from a poor family, and I was embarrassed to hear that my dad told coaches he couldn’t afford my training or that he couldn’t take me to a game because we didn’t have a car,” said Moreno, whom DiMauro trained and later played for Ramos in the U-20 national team. “I know exactly what some of these kids go through. I’ve lived their lives.”

Ramos, a midfielder with 81 appearances for the U.S. national team, including the 1990, 1994, and 1998 World Cups, and an inductee into the Hall of Fame, noted that while there are three well-established soccer academies in New Jersey — the Red Bulls Academy in East Hanover, the Players Development Academy in Somerset, and the Cedar Star Academy in Tinton Falls — a newcomer like Xolos has a definitive role to play in talent evaluation.

“The three academies start from the top down,” Ramos said. “But smaller clubs like Xolos Academy can step in to identify talent from the bottom up, from 5 and 6-year-olds, and then hope that when these same players are 10 or 11, they can move on to larger academies that can offer national-level competition.”

Ramos added that the most significant challenge faced by the three soccer academies isn’t subsidizing training for financially struggling players. Instead, it’s providing transportation for athletes living within the state who can’t afford long-distance travel to attend practices and games.

“These academies can’t afford to buy a van or hire a bus to service so many players scattered across the state,” he said. “This makes the work of smaller academies that focus on local players even more critical.”

DiMauro mentioned that the coaching staff members organized to share their vehicles and transport many of the 80 players, aged 8 to 18, to practices and games. The club also created an outdoor training site in a South River field closer to the residences of many Spanish-speaking players.

One of these players is Xavier Tapia, a 12-year-old defender, belonging to the 80% of Spanish-speaking players from a dozen Latin American countries in the Xolos New Jersey program (the remaining players are white and typically middle-class residents from nearby cities and towns).

Recently, before a morning practice, Tapia pointed upwards, towards two posters on a facility wall, depicting Moreno in action. “My dream is to be a professional like him,” Tapia said.

Moreno returned home last month to visit his family and friends after Tijuana was eliminated from the playoffs. He made a stop at Academias Cerca de Mi Ubicación, the Xolos training center, greeting DiMauro and his son, Phil, a coach assisting his father in managing the academy.

“I wish there was a place like this when I was young,” Moreno said as he walked beneath a large mural featuring a xolo, a hairless dog breed serving as the Tijuana team’s logo, alongside a pit bull, the logo of his New Jersey cousin.

“I guess the players here see me as an inspiration,” Moreno said. “They look at me and think, ‘If he could do it, I can too.'”

Moreno helped forge the relationship between DiMauro and the Xolos in Mexico. Now, both organizations hope to reap the benefits of an almost 5000-kilometer-long channel connecting Tijuana, one of the world’s busiest border cities, with Cliffwood, a community that was once part of a Dutch settlement dependent on its ships.

“Believe me, there are excellent players in this area just waiting to be discovered,” Moreno said. “All they need is the opportunity to be seen and prove themselves.”